The aim of understanding welfare state developments has been of great interest in comparative social policy. These analyses mainly focus on affluent capitalist democracies excluding the former socialist states. Recently the formation and development of the welfare state among East Central European countries (ECE) has brought much attention. The integration of these states to welfare state examinations is relevant because of their extensive social policies. In this paper we analyse the different patterns of generosity trends among welfare regimes.

The concept of welfare state and welfare models

The concept of welfare state is highly debated and discussed in the economic literature, moreover, there is no universally accepted definition, nor does there exist one that suits all purposes (including the measurement issues and the compilation of statistics). Barr (1987) emphasized that the concept of welfare state can be understood as a mosaic, “with diversity both in its source and in the manner of its delivery” (p. 5).

The use of the expression ‘welfare’ has always been inexact, that is why the clear description is needed what will be the object of this paper. The primary focus of the study is on the welfare state as a form of social insurance guaranteed by the state with a special focus on welfare efforts.

In our analysis welfare state can therefore be thought of “as a shorthand for the state’s role in education, health, housing, poor relief, social insurance and other social services” (Ginsburg 1979, pp. 3) in developed capitalist states. Several different combinations of programmes and policies can be understood as the welfare state. Within this diversity there are a few clear clusters, which are broadly distinctive types of the welfare states. They represent prototypes or can be understood as ideal types, called welfare regimes or welfare state models. The different welfare regimes form different “worlds of welfare capitalism” described by Esping-Andersen (1990), representing totally different worlds being sharply differentiated from one another (Inglot, 2008, pp. 4-5).

The three different types defined by Esping-Andersen (1990) was modified by Sapir (2006) who in order to highlight the differences among the social policy models made the following four different clusters. (1) The Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands represent for the highest levels of social protection expenditures and universal welfare provision with active labour market policy instruments (social democratic model in Esping-Andersen typology). (2) Anglo-Saxon countries: Ireland and the United Kingdom plus the United States added to Sapir’s typology feature relatively large social assistance of the last resort and salient activation measures (liberal model in Esping-Andersen typology). (3) Continental countries: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Luxembourg rely extensively on insurance-based, non-employment benefits and old-age pensions (corporatist-statist or conservative model in Esping-Andersen typology). (4) Mediterranean countries: Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain concentrate mainly on old-age pension and allow high segmentation of welfare entitlements.

Central and Eastern Europe constitutes a separate cluster, because the countries of this region has been in a transitional state with a wide diversity of situations, whose definitive characteristics are not yet clearly specified (André, 2006). However Aidukaite (2004, 2011) argues that post-communist European countries form a singular welfare state type because of their distinct institutional similarities, the debate on the emergence of the post-communist (or CEE) type of welfare state has been inconclusive (Adascalitei, 2012). According to the inconclusiveness of the post-communist welfare state literature in the following the post-communist countries will be grouped together into one cluster, as a first step, then in further research separate clusters will be constructed based on their different features.

Measurement issues

There is a wide range of literature dealing with the measurement problems of welfare indicators. In the forthcoming welfare state generosity ratio will be used in order to analyse welfare efforts, however in purely monetary terms.

Aggregate social spending as a percentage of GDP is one of the most widely used measure of the “welfare effort” that governments make on behalf of their citizens, and changes in this measure provide a useful hindsight into the nation’s continuous commitment to welfare (Castles, 2004). With the introduction of generosity ratios we broaden the general picture of social expenditure developments while taking into account the population in need, but this methodology still remains within the framework of quantitative spending based welfare state research. However comparative welfare state research is mainly based on public spending data, scholars have long emphasized the shortcomings of this methodology and the need for more qualitative approaches (Scruggs, 2007).

Welfare state generosity ratio is a simplistic measuring rod for assessing how well modern welfare states cope with the self-contradiction that while providing services they are generating at the same time increased demand for them. Two categories are mostly cited in the literature as most important factors affecting the welfare state, namely the aging population and the increasing level of unemployment (equal together the dependent ratio of the population). Based on the method of dividing the aggregates of social expenditures by the percentage of dependent population (population aged sixty-five and over and registered unemployed people) a simple ratio can be computed, measuring the generosity of welfare. Theoretically it can be interpreted as the percentage of GDP received in welfare spending for every 1 per cent of the population in need (Castles, 2004:36). Welfare state generosity ratios put the post-communist EU member states[i] on the map of the worlds of welfare states and allows us to compare welfare state policies of the country groups.

There are two obvious deficiencies with this measurement. First, an average figure for each country can be calculated without taking into account the different sections of the population in need. Second, expenditures are delivered to only two categories of welfare recipient (Castles, 2004). However the described method is a really simplistic way to measure the performance of the welfare state by neglecting several other important factors, general trends can be drawn to compare different models.

Analysing welfare state generosity of the different welfare state models

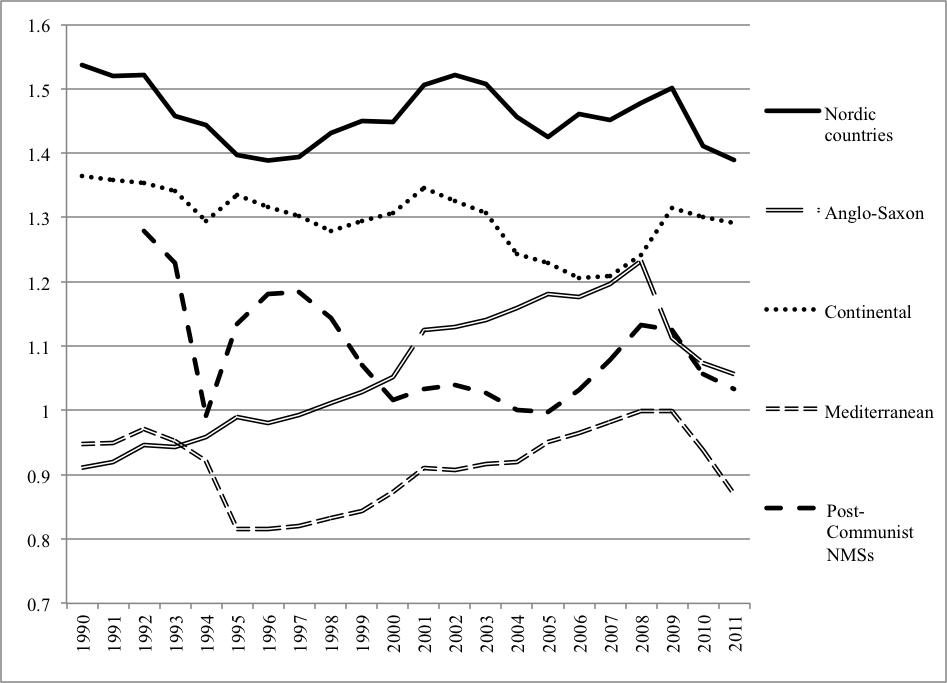

Figure 1. Welfare state generosity ratios (mean values) for the different welfare state models (1990-2011)

Source: European Commission (2012): Statistical Annex of European Economy. Spring 2012. Table 61 (Social transfers in kind) and Table 64 (Social benefits other than social transfers in kind; general government; ESA 95, percentage of gross domestic product at market prices)

Analysing the result for the different models it can be concluded that the generosity ratio of them all have converged (Firgure 1) before the crisis, until 2008. By 2010 the Anglo-Saxon and the Post-Communist model have reached similar generosity level, meaning a significant cut for both of them, however there were salient variation in their generosity trends. Until the outbreak of the 2008 crisis, the welfare state generosity ratios of the new EU member states were converging towards the Continental countries, as the Liberal countries’, but the crisis has brought a radical change for their generosity trends. The Mediterranean countries after significant improvement (as a consequence of the EU accession) started to cut back welfare expenditures enforced by the crisis, reaching almost their lowest pre-accession level. The mean value of generosity for the Nordic countries went through significant decrease because Sweden and Norway radically cut back these types of expenditures, while for other Nordic countries this ratio has been increased.

Since the 1990s, the coefficient variation has become significantly lower for all groups, reaching approximately similar (around 10 per cent) value in 2008, it means that the construction of the clusters have remained adequate during the whole period. Consequently to the crisis coefficient variation of the Nordic and Continental countries have become lower, while for the other groups growth of the given measure has been accelerated, which means different social policy reforms. For the Post-Communist welfare states coefficient variations of their welfare state generosity ratios were significantly higher, especially for the period of 2000-2006, since 2006 social policy differences within this group have not been salient any more. Among Post-Communist welfare states, Hungary has reduced its generosity level to the greatest extent, from 1.42 in 1992 to 0.94 in 2011. In 2008 several countries within this group had generosity levels above 1, and as a consequence of the crisis almost all of them (except Slovenia and the Czech Republic) have reduced their generosity, social spending. The welfare system exhibits a large extent of path-dependency which makes the implementation of any social policy reforms even more difficult for these countries.

Further questions

On the one hand, as Aidukaite (2004, 2011) argues post-communist European countries form a singular welfare state based on their distinct institutional similarities and communist legacies. Still the debate on the emergence of the post-communist (or ECE) type of welfare state has been inconclusive, then the understanding of the variety of Post-Communist welfare states is essential. In fact diversity within this group of countries is as much present as in the EU15, looking at the significant differences of welfare efforts. However ECE welfare states do not easily “lend themselves to classification into a pre-existent typology” (Adascalitei, 2012, p. 60), in further research their classification will be the next step.

On the other hand, to understand the differences in generosity trends the investigation of the background factors are crucial. The different impacts of low expenditures versus high share of the dependent population have to be analysed on a more detailed way in order to establish a more comprehensive picture of the different models.

Ágnes Orosz

References

Adascalitei, D. (2012). Welfare State Development in Central and Eastern Europe: A State of the Art Literature Review. Studies of Transition States and Societies, 4(2), 59-70.

Aidukaite, J. (2004). The Emergence of the Post-Socialist Welfare State: The Case of the Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Södertörns högskola, Stockholm: Elanders Gotab.

Aidukaite, J. (2011). Welfare reforms and socio-economic trends in the 10 new EU member states of Central and Eastern Europe. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 44(3): 211-219.

André, C. (2006). Welfare regimes and A. Sapir’s paper: "Globalisation and the Reform of European Social Models". Paper prepared presented at the workshop Concepts of the European Social Model, Vienna, 9 June 2006.

Barr, N. (1987). The Economics of the Welfare State. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson

Castles, F. G. (2004). The Future of the Welfare State: Crisis Myths and Crisis Realities. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

European Commission (2012). Statistical Annex of European Economy. Spring 2012.

Ginsburg, N. (1979). Class, Capital and Social Policy. London: Macmillan

Inglot, T. (2008). Welfare states in East Central Europe, 1919-2004. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press

Sapir, A. (2006). Globalization and the Reform of European Social Models. Journal of Common Market Studies, 44( 2), 369-390.

Scruggs, L. (2007). Welfare State Generosity Across Space and Time. In: Clasen, J. & Siegel, N. A. (eds.). Investigating Welfare State Change: The ‘Dependent Variable Problem’ in Comparative Analysis. Cheltenham, UK & Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing. Chapter 7. pp. 133-165.

[i] The new EU member state countries except Malta and Cyprus, because these eight countries have similar historical background and share communist legacies in their social policies.