Over the past two decades, China's share of the world economy's total FDI stock has grown rapidly. While in 2000 the country's share was negligible, by 2023 it accounted for nearly 7% of the total stock, according to UNCTAD data. This rapid growth contrasts with the stagnating share of the other BRICs and the slightly or significantly declining share of the leading developed economies (especially the US). Since 2009, China has been the "podium" country in terms of annual outward FDI inflows every year, mostly behind the US and ahead of Japan in the ranking. Nevertheless, there have been years when China has been the largest source of outward FDI in the world economy: for example, in 2014 or 2020. In 2022, China accounted for more than 10% of total annual outward FDI in the world economy, and in 2023 for more than 9.5%. Including Hong Kong, these shares are more than 17% and more than 16% respectively (UNCTAD). (Further growth is likely to continue, as outward FDI in China accounted for 16% of GDP in 2023, compared to an OECD average of 52% and even around 20% for Central and Eastern European countries.)

Such an increase in outward FDI is impressive even when taking into account the many problems with the FDI data reported by China. Chinese multinationals tend to set up special purpose entities in intermediary countries, most often Hong Kong, and 'channel' their outward investment through them. In some cases, the capital returns to China (round-tripping), in other cases it continues to its final destination in third (or even fourth, fifth etc.) countries. Thus, we have limited reliable information on the final destination countries of the originally Chinese FDI and on the actual size of Chinese FDI. On the other hand, it is suspected that the majority of outward FDI in Hong Kong is owned by Chinese firms.

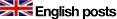

Figure: FDI stock from China and China+Hong Kong as % of GDP in selected OECD countries, 2014 and 2022

Source: OECD, for UK: Office for National Statistics; Hungary 2022 data: MNB; Germany and UK: 2021 data instead of 2022

Reliable data disaggregated by ultimate Chinese investors are only available for a few developed OECD countries, and in virtually all of them Chinese FDI increased between 2014 and 2022. The United States has the highest stock of Chinese capital, while in Europe France, Germany and Switzerland are the most important destinations in terms of absolute investment. When the size of economies is also taken into account, Hungary and Switzerland stand out in terms of the size of FDI from China relative to GDP. If we also take into account the different "FDI exposure" of each economy, the different role of FDI in each country, Hungary also shows the highest share of Chinese FDI in total FDI in 2022: almost 5%. Based on various analyses, there is one other European country worth looking at. Serbia has recently seen a surge in Chinese projects and has become a major destination for Chinese FDI in Southern Europe. Chinese capital is coming to the country mainly through brownfield acquisitions of old industrial capacities, such as the Smederevo steel plant and the Bor metallurgical and mining combine, and greenfield investments, such as the Linglong vehicle tyre factory in Zrenjanin. In 2022, about 10% of total FDI will come from China (including Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan, according to the Bank of Serbia's specific interpretation). This will make China the 5th largest investor in the Balkans in 2022.

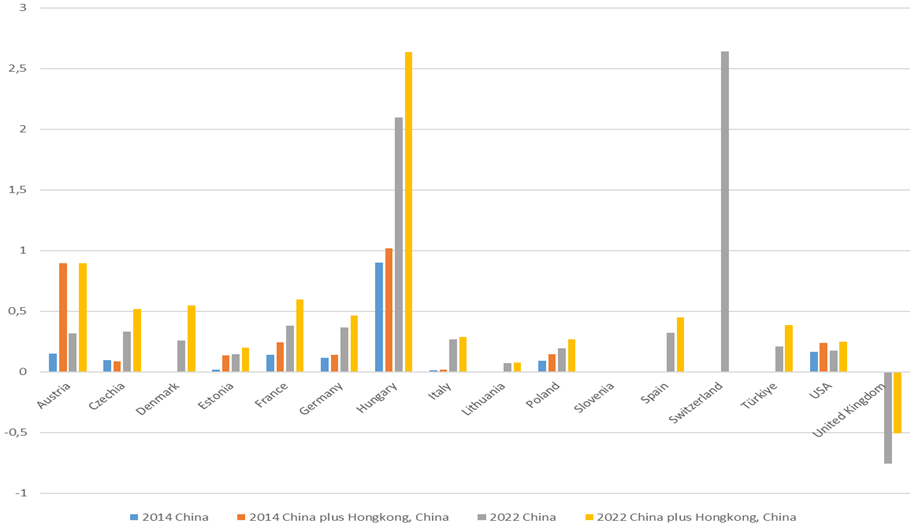

The latest figures for 2023 and 2024 and announcements of FDI projects in China indicate a continuation of these trends. In 2023 and 2024, Chinese investment in Hungary, mainly in electric vehicles, continued to grow, accounting for 44% of all Chinese FDI in Europe, making Hungary the number one destination and China the number one investor in the country last year. The previous leading European destinations (Germany, France and the UK) accounted for about one third of Chinese annual FDI in Europe. (In Serbia, China was the largest investor in 2023 with an investment of €1,373 million, accounting for nearly one third of total annual FDI inflows in the country.)

China against world trends

The shift in Chinese activity is at odds with the FDI trends that are becoming increasingly prominent in the global economy. Globalisation has been transformed by changes driven by technological advances, (geo)political developments and sustainability requirements. As a result, the growth of FDI (and associated global value chains) has declined or stagnated relative to GDP or foreign trade growth in the longer term. Geopolitical considerations have also become more important than economic ones in FDI: the share of investment in 'friendly' countries has increased significantly, with multinationals increasingly locating strategic activities closer to home. This is causing volatility in FDI relations and the marginalisation of traditional FDI factors, as well as reducing diversification opportunities for host economies. There is a divergence between FDI in manufacturing and FDI in services, with services becoming increasingly dominant, including services linked to manufacturing activity. And in manufacturing, FDI in sectors that support sustainability has grown rapidly, in effect almost the only capital available on the 'supply side'. Examples include environmental technologies and e-battery and e-car manufacturing.

Compared to these global trends, China's foreign direct investment is partly moving in a different direction. First, Chinese FDI has been growing significantly in recent years, driven by the changing growth trajectory of the Chinese economy, significant domestic overcapacity and stagnating domestic consumption, and thus increasing reliance on external export markets. In the past, Chinese investors were attracted by raw materials and energy resources in developing countries, partly through acquisitions and partly through greenfield investments, while in developed countries they mainly bought technology and brands, and so the dominant mode of entry was through acquisitions. However, in the last two to three years, with the gradual closure of export markets and the rise of protectionism, the mix of motives has changed: while access to raw materials and technological resources remain important, new motives have emerged. One important new motivation is the international expansion of Chinese digital brands and platforms, which is driving China's international expansion in the cultural and technological fields. Alibaba, TikTok and JD.com are going global to enter new markets and find new audiences. Bytedance, the parent company of TikTok, was the fifth most active Chinese investor last year, announcing nine FDI projects. These included new offices in Argentina, Colombia, Denmark and Kenya; a research and development centre in Sydney, Australia; and a $1.3 billion pledge to build three new data centres to comply with EU data transfer legislation.

Avoidance of increased customs duties

An even more important new motivation is the growing number of so-called tariff jumping FDI. Exports are the way out for Chinese companies in the face of weakening domestic demand, but solvent developed markets are increasingly using protectionist measures to shield their producers from (some argue artificially) low-priced Chinese imports. It is thus becoming increasingly important for China to bypass protectionist measures and supply local or 'friendly country' production and exports to targeted but closing developed and in some cases developing markets (e.g. Brazil or Indonesia). The Chinese government is also providing significant support to these efforts. Related to this, developing countries have also become important export markets and production sites for global value chains led by Chinese companies. (The problem is that the host country often profits little from this: all the parts and components, and often even the workers, are imported from China. This also raises questions about the extent to which the goods thus produced in such a way meet the already poorly defined and enforced rules of origin requirements, and thus qualify as products that can be exported to closing markets at preferential tariffs.) In other words, developed markets are partly replaced by these developing markets, and from there, Chinese producers can also bypass the protectionist "walls" erected by the developed countries. The change also affects the mode of entry: there is a clear preference for greenfield investments. A good example is Mexico, from where the US market is easily accessible thanks to the USMCA agreement and geographical proximity. Between 2022 and 2023, Chinese FDI there increased by 57%. As a result last year Mexico replaced China as the leading US trading partner for imports of goods. Vietnam is another good example: in 2023, Chinese FDI there also set records, while Vietnam is the leading foreign trade partner of both the US and the EU, and has a free trade agreement with the EU since 2020.

Figure: Distribution of Chinese FDI inflows in the European Union in 2023 (%)

Source: Kratz, A., Zenglein, M. J., Brown, A., Sebastian, G., Meyer, A. "Dwindling investments become more concentrated - Chinese FDI in Europe: 2023 Update", MERICS Report, 6 June, 2024,

The large investments that are also planned in "friendly" Hungary are part of this process. China has announced EUR 7.6 billion of FDI in Hungary in 2023, making it the largest source country last year. Among electric vehicle investments in 2023, BYD stood out, but other smaller-scale investments (e.g. Evoring, Baolong, Sunwoda, Huayou Cobalt, Eve Power) and investments in other sectors (e.g. CPMC, Wasion, Jiecang Linear Motion) also contributed to China's top ranking last year. According to data of the Hungarian National Bank, China was the 8th largest investor country in Hungary in 2022 (6th with Hong Kong). Thanks to projects in 2023 and 2024, it is likely to "jump up" to 2nd-5th place and increase its share in total FDI in Hungary to around 10%, approaching the figures for Austria, South Korea or the US. These investments also show the so-called "tariff jumping" motivation and are of the export-platform character. Their capacities are so large that they are clearly not looking to supply the Hungarian market but the EU market. For example, the planned annual capacity of BYD's car plant in Szeged alone is 200 000, while the number of new car sales in Hungary is around 100 000 per year.

The increase in FDI inflows in Hungary has thus been from the most available sources and sectors, although the growth impact so far has been surprisingly low. At the same time, given the background, it is questionable what the consequences for the Hungarian economy will be in the future. On the one hand, increasing sectoral specialisation increases the vulnerability of the economy. On the other hand, the increase in geopolitical tensions is not conducive to the continued smooth access of these capacities to their intended export markets. Thirdly, the reliance on Chinese components, sub-assemblies and R&D (and on not local labour), which, based on experience to date, is much stronger among Chinese investors than among other investors, suggests that the positive impact on the Hungarian economy will be limited or even non-existent.

Magdolna Sass

Translation of the post of KRTK Portfolio-blog, published on the 1st of September, 2024 at https://www.portfolio.hu/krtk/20240901/magyarorszag-europai-ellovas-a-kinai-befektetesek-teren-de-ki-jar-ezzel-jol-706459