Chinese companies have increasingly been targeting Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries in the past one and a half decades, while diplomatic relations are also on the rise. This development is quite a new phenomenon but not an unexpected one. On one hand, the transformation of the global economy and the restructuring of China’s economy are responsible for growing Chinese interest in the developed world, including the European Union. On the other hand, CEE countries have also become more open to Chinese business opportunities, especially after the global economic and financial crisis with the intention of decreasing their economic dependency on Western (European) markets. Here, China can benefit a lot from the EU’s core and peripheral type of division. For China, the region represents dynamic, largely developed, less saturated markets, new frontiers for export expansion, new entry points to Europe and cheap but qualified labor. This adds up to less political expectations, less economic complaints, less protectionist barriers and less national security concerns in the CEE region compared to the Western European neighbors. CEE countries' disappointment coming from the slower-than-expected catching-up processes to Western Europe also resulted in these countries’ turning towards the East.

Chinese economic presence is indeed substantial in Hungary in regional comparison. In the past one and a half decades Hungarian governments have increasingly perceived China as a country which could bring economic benefits through developing trade relations, growing inflows of investment and recently also through infrastructure projects.

The above-mentioned trends together with the 16+1 cooperation between 16 CEE countries and China have drawn the attention of Western diplomats, scholars and media to these intensifying efforts and their potential implications on the EU or even globally. Therefore, it is worth to examine China's growing economic presence in Hungary through China's trade, investments as well as infrastructure-related projects here, in order to show that - although Chinese economic influence is on the rise - in reality, it is far from being decisive yet. On the contrary, EU's position in these fields is almost unshakable.

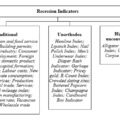

Chinese trade volumes have steadily increased in the last one and a half decades, particularly after 2004 and 2008 (2004 was the accession date to the EU while 2008 is the year of the economic and financial crisis).

Although trade relations are indeed on the rise, it has to be emphasized that the vast majority (around 80 per cent) of Hungary’s export still targets the countries of the European Union, mainly Germany (25-30 per cent) and Hungary’s export to China represents less than 5 per cent. Similarly, a bit less than 80 per cent of Hungary's import is coming from the EU, more than 25 per cent from Germany, while only around 6 per cent from China.

Investments

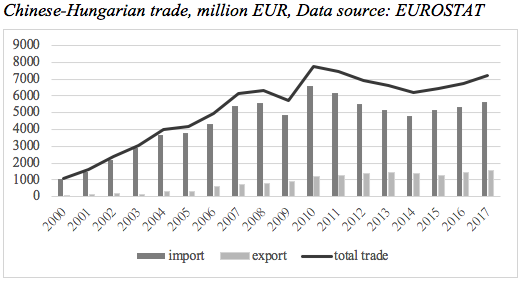

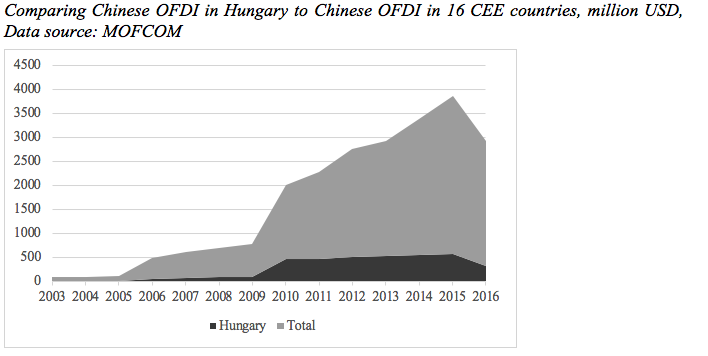

Chinese outward foreign direct investment has also been increasing in every CEE countries and - as can be seen on the graph below - Hungary is among the most popular destinations.

In some cases, FDI amount is far greater when taking into account ultimate investors instead of direct ones since a significant portion of Chinese investment has been received via intermediary countries or companies, therefore it appears elsewhere in statistics. In the case of Hungary, the difference between “direct” and “ultimate” data is especially large for China: while Chinese (MOFCOM) statistics shows a rather modest stock of Chinese investment in Hungary (314 million USD), the Hungarian National Bank - where statistics are broken down according to ultimate investors - knows about 1782 million USD. Nevertheless, the dominance of EU partners has to be highlighted here, too: more than 75 per cent of foreign investments are coming from EU countries, more than 25 per cent from Germany, while only 2.4 per cent from China. This data is the highest in Hungary in regional comparison, still far from being decisive.

Although Chinese multinational companies represent a relatively small share, they have saved and/or created jobs (especially Wanhua, Huawei) and contributed to the economic growth of Hungary with their investments and exports. Furthermore, many of them (e.g. Lenovo, ZTE, Huawei, Bank of China) have turned their Hungarian businesses into European regional hubs of their activities. Recently, the Miskolc-based starting engine- and generator-producer business of Bosch was acquired by a Chinese company, while CEE Equity Fund, established together by the Hungarian and the Chinese Exim Bank, purchased a private university and a telecommunications service provider.

Infrastructure

Besides being a potential hub for Chinese products in the European Union, Chinese companies expressed their interest in several Hungarian infrastructure-related investment in recent years, such as plans to transform Szombathely airport into a major European cargo base or develop the infrastructure of the Debrecen airport. None of them have been realized so far. The project to modernize the Belgrade–Budapest rail link is a recent example of this kind, planned under a new framework, China’s Belt and Road initiative.

China’s motivations are easy to understand, as the New Silk Road project will allow it to expand its political and economic sphere of interest: once the alternative transport routes are completed China will be in a more favourable strategic position, will have more and more alternative transport routes, can reach their target markets easier and faster and will be able to work off some of the industrial overcapacities accumulated in recent years. In addition, these projects may provide a reference for further Chinese investment in the broader region, especially in the more developed part of Europe.

Hungary was the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding with China on promoting the Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road, during Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Budapest in June, 2015. The Hungarian government was very keen on the railway project and when it signed the construction agreement in 2014, Prime Minister Orbán called it the most important moment in cooperation between the European Union and China. Infrastructure development is indeed a hot topic in all CEE countries; however, there are other resources – for example EU funds – to finance them. Therefore, a more interesting - and for the time being unanswered - question is: what motivates the Hungarian side in building infrastructure with Chinese companies, using Chinese credit to finance it? Here, the political factor seems to be more important than the economic rationale.

Wrapping up

The China-Hungary relationship is a significant one, however, it shall not be interpreted as a strategic and influential alliance that could affect world politics or economy, for several reasons.

When compared to China’s economic presence globally or in the developed world, its economic impact on Hungary is relatively small: Hungary is still highly dependent on both trade and investment relations with developed, mainly EU member states while China represents a minor (although increasing) share. From Chinese point of view, as far as trade or investment statistics are concerned, Hungary is also far from being among the most important partners of China (within the EU, for example, Germany, the UK and France accounted for more than half of total Chinese investment value last year, while the whole CEE region received less than five per cent).

China still has to learn a lot on how to do business with Europe, even if it is Central and Eastern Europe: it can be seen from its first infrastructure-building attempts in CEE, especially from the Budapest-Belgrade railway project, that China tries to bring in the same package as in the developing world, Southeast Asia or Africa, not considering the different – and sometimes very strict – rules and regulations or standards of the EU.

In its current stage, the China-Hungary cooperation is more like a new relationship with full of potential. Exploiting such potential will require further steps and careful - economic as well as political - considerations from both sides.

Ágnes Szunomár

This text was written in the framework of the project "Comparative analysis of the approach to China: V4+ and One Belt One Road" implemented by IWE (Hungary) in cooperation with PSSI (Czech Republic), IAS (Slovakia), BFPE (Serbia), CIR (Poland), and supported by the International Visgerad Fund (IVF).