In what follows Future Forests’ LULUCF researchers David Ellison, Mattias Lundblad and Hans Petersson report on the results of a panel that was organized and held at the annual Conference of the Parties meeting (COP18/CMP8) in Doha, Qatar.

In the context of the UNFCCC Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) call for views on the potential for more comprehensive accounting (decision 2/CMP.7, paragraph 5.1) and ongoing discussions and debates among observers and Parties to the convention on how to improve the overall framework, a broad range of ideas and models were discussed on the broad framework for mobilizing Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) in the climate policy framework.

Aulikki Kauppila and Giacomo Grassi, DG Climate Action and the Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Commission, LULUCF in the EU Climate Policy Framework

The European Commission is currently taking unprecedented steps forward to harmonize the LULUCF carbon accounting approaches across the Member states and is likewise considering the inclusion of mandatory reporting requirements on Cropland and Grazing Land Management (CM and GM) in the EU framework (EC 2012). The European Parliament and the European Council adopted this measure in March 2013. Likewise, the EU is and will continue to consider the continued integration inclusion of LULUCF in its climate policy framework, but remains resistant to the idea of incorporating more comprehensive accounting in the EU’s Emission Trading Scheme (EU ETS). The currently favored model would maintain strict divisions between emission reduction targets in the EU ETS sector, the non-ETS (or effort-sharing) sector, and agriculture and forestry (LULUCF) (EC 2012).

Hans Nilsagård, Swedish Government Representative, Swedish Negotiating Team (Swedish Advisor to the Swedish Ministry for Rural Affairs), LULUCF and the Climate Policy Framework

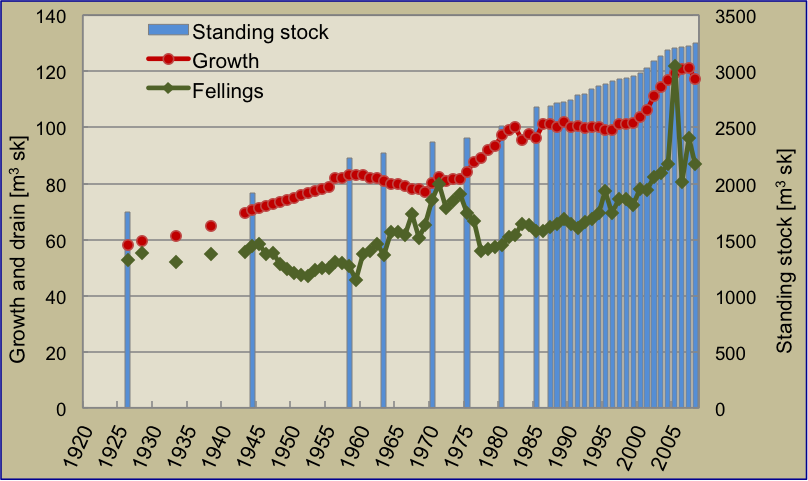

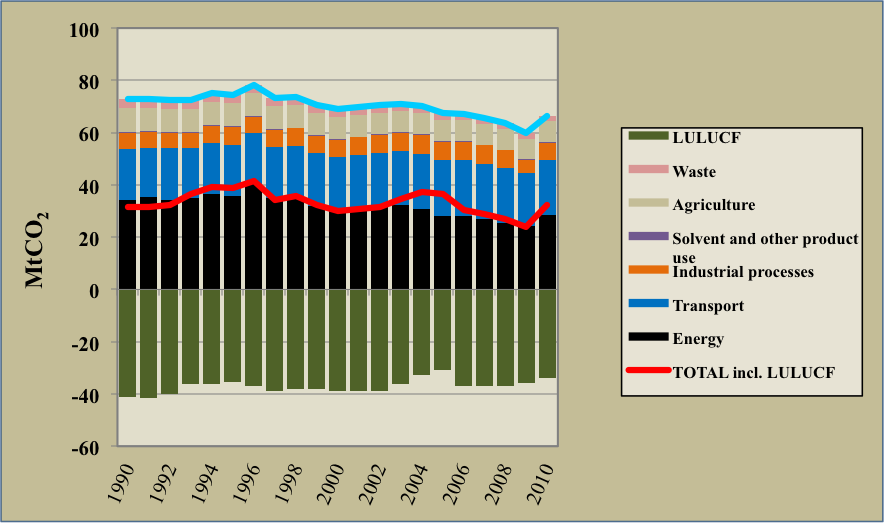

Sweden has historically witnessed a significant amount of increased forest growth. As illustrated in Figure I, total available forest (carbon) stocks have approximately doubled since about the mid-1920’s. As illustrated in Figure II, total forest-based carbon sequestration (net removals) represents a large share of total Swedish emissions/removals. Despite significant carbon sequestration potential in the Swedish forest management sector, Swedish negotiators in the UNFCCC/Kyoto framework are hesitant about dramatic changes in the LULUCF carbon accounting framework and, in particular, about creating a larger role of forest management in that framework. In particular, concerns were voiced about the turning the climate change mitigation strategy into a forest-based strategy focused entirely on the environment. Climate change mitigation strategies must focus on the role of fossil fuel energy use. Moreover, uncertainty plays a big role in the LULUCF sector, making it more difficult to transfer a large share of the climate effort to this sector.

Figure I: Standing Stock in Swedish Forests, 1920-2010

Figure II: Total Swedish Emissions/Removals, 1990-2010

Derik Broekhoff, Climate Action Reserve, The California Forest Project Protocol (CA_FPP)

California, on the other hand, has gone in a different direction. The California Forest Protocol, part of the larger California carbon trading scheme, was first introduced in 2007 (the California carbon trading scheme went into effect in January 2013) and could potentially have a large and important impact on future forest growth in California and potentially the greater United States. In contrast to the UNFCCC based Kyoto framework, the California model remains independent and employs distinct carbon accounting procedures. Most importantly, the California model employs only a zero baseline from future growth is measured, and then allows carbon credits to be claimed on any and all forest-based carbon sequestration (net removals) above the baseline. All forest-related activities are accepted in this framework, including forest management.

This model lies in stark contrast to the UNFCCC-based Kyoto framework where most of the emphasis has been placed primarily on ARD activities (Art. 3.3 net of afforestation, reforestation and deforestation), and where upward ceilings on the potential claim of forest-based carbon credits are imposed on Forest Management (Art. 3.4). Though the Durban LULUCF agreement raised the ceiling to 3.5% of 1990 emissions (excluding LULUCF) from 3% of 1990 emission or 15% of the net annual harvest (whichever was smaller), the California model imposes no such restrictions either on its ARD-type segment or on the forest management sector. Moreover, there are strong (100 year) commitments in the California Forest Protocol to ensure the permanence of increased forest cover, including both an insurance mechanism to compensate for natural disturbances and a sanction mechanism for ‘avoidable’ cases of deforestation. All carbon credits are fully tradable within the California carbon trading framework.

Louis Verchot, CIFOR, Wetlands and LULUCF Carbon Accounting

Wetlands and their potential inclusion in the UNFCCC/Kyoto reporting and accounting frameworks are the subject of increasing attention. As an important contributor to carbon emissions, wetlands (in particular peatlands) have been of particular interest in countries like Indonesia where the powerful economic incentives attached in particular to palm oil (but also to other forms of agricultural production) have led to the extensive, draining, burning and general degradation of existing peatlands. Moreover, current definitions of forest (in Indonesia and also in the larger IPCC framework) have been conceived in ways that do not incorporate wetlands or peatlands. One of the principal barriers to including wetlands and peatlands, however, has been the lack of an agreed methodology for measuring carbon stocks and emissions in peatlands. Current expectations are that an appropriate methodology will be agreed upon in the IPCC framework within the next year or so, paving the way for the inclusion of wetlands in either voluntary or mandatory carbon accounting and reporting frameworks.

Sebataolo Rahlao, Energy Research Center, University of Cape Town, On the AFOLU/ LULUCF and REDD frameworks in S. Africa

Developing world countries face a number of additional hurdles and tasks, not the least of which is establishing relevant baselines for estimating the growth of future forest-based carbon stocks. While South Africa, for example, has made significant progress on this front and has incorporated AFOLU elements into its general carbon mitigation scheme framework, the country has likewise faced a number of difficulties. The most important of these is the fact that some areas of natural land cover do not easily conform to currently accepted IPCC definitions of forest cover and/or biomes. In particular, South Africa possesses one of the largest areas of highly volatile and thus potentially vulnerable non-forest carbon stocks in the world. Rahlao (2012) notes that South Africa ranks among the top ten countries “with volatile carbon (4.1 GtC) stocks stored in other landscapes, such as grasslands, that could be readily released into the atmosphere through land use change”. These stocks dwarf by far the total amount of annual carbon flows in AFOLU -~28MtCO2e. Since these lands, however, do not fall under the conventional, accepted definitions of “forest”, they naturally test the barriers of the rapidly developing systems for engaging and mobilizing LULUCF and AFOLU in the climate policy framework.

David Ellison, Mattias Lundblad and Hans Petersson, IWE and SLU, The Incentive Gap after Durban

The current UNFCCC-based Kyoto mechanism fails to establish an adequate framework for incentivizing the full carbon value of forest-based resources and thus for fully mobilizing increased forest growth. To illustrate the consequences of the new 3.5% cap, we assume a potential 20% increase in forest growth between CP1 and CP2. Average in 2008 and 2009 across the Annex I countries was approximately 3% per year. 7 years of growth over the period 2013-2020 would come to approximately 21%. Weighted across all Annex I countries, however, the average rate of growth in 2008-2009 is approximately 1.2%/yr. The relative size of the Incentive Gap in this illustration is in part a function of the degree of relative growth we assume. In another simulation, Grassi et al (2012), for example assume only 10% growth.

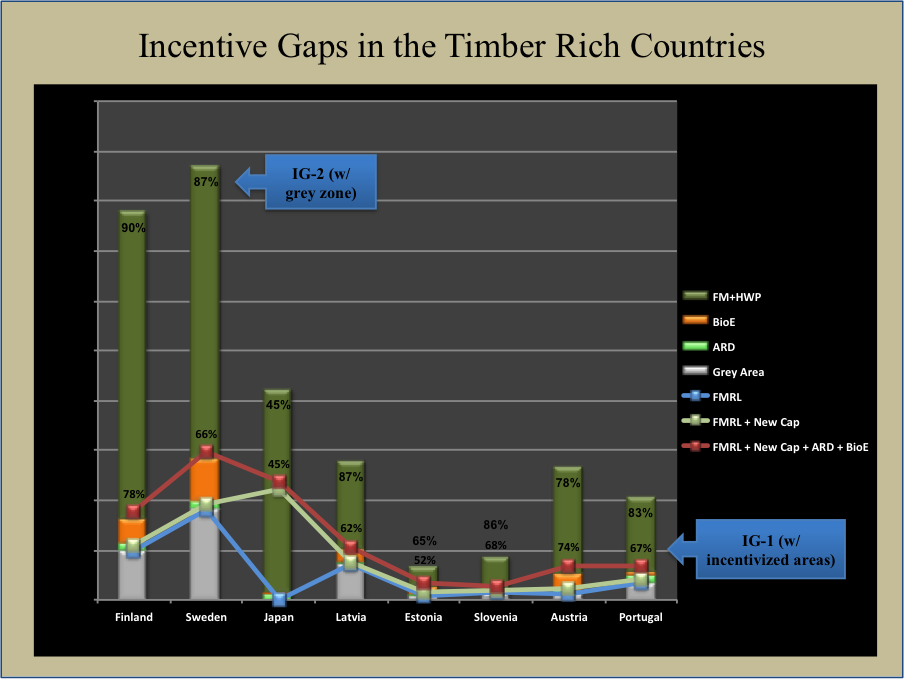

Figure III provides a scenario measuring the Incentive Gap (IG) (Ellison et al 2011; 2013) against an estimate of potential future growth across a number of the Parties to the Kyoto agreement. Several points are evident from the illustration. First, for the timber-rich countries below, the cap (space between the blue and light green lines) represents an extremely small share of the total potential forest growth. Second, the total share of “incentivized” forest growth—IG-1 (the space up to the red line)—represents a relatively small share of the total potential forest growth. Third, whether one should consider the space up to the new Forest Management Reference Level (FMRL, blue line) as incentivized is likewise problematic. Falling below the blue reference line will yield debits, while forest growth represented that falls in the “grey area” is not eligible for carbon credits. In this sense, the FMRL is only partially incentivized. Including the FMRL grey area in the estimate of the non-incentivized share yields a very sizable incentive gap—IG-2. This data raises important questions about the relative value of both the cap and the FMRL for promoting forest growth and forest-based carbon sequestration (net removals). Ellison et al (2011, 2013) argue that in order to make the UNFCCC/Kyoto based LULUCF carbon accounting framework a genuine promoter of forest growth, it is necessary to eliminate all restrictions on carbon credits such as the cap and the FMRL. The authors suggest the FMRL might better be used as a tool for raising the general emission reduction commitments of Kyoto Parties.

David Ellison, Mattias Lundblad and Hans Petersson

First published in the Future Forests News Archive, May 6th, 2013.

Further reading:

EC (2012). “Impact Assessment on the role of land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) in the EU's climate change commitments.” SWD(2012) 41 final.

Ellison, David, Hans Petersson, Mattias Lundblad and Per-Erik Wikberg (2013). “The Incentive Gap: LULUCF and the Kyoto Mechanism Before and After Durban”, Global Change Biology – Bioenergy.

Ellison, David (2012). “On the Future of REDD+ and the Carbon Market”, Blog Posts from the Energy Research Center, Energy Research Center, University of Capetown, Nov. 7th.

Ellison, David, Mattias Lundblad and Hans Petersson (2012). “Open Letter to Mr. Asger Olesen and DG Climate Action”, EurActiv.com, Oct. 2nd.

Ellison, David, Mattias Lundblad and Hans Petersson (2011). “Carbon Accounting and the Climate Politics of Forestry”, Environmental Science & Policy. 14, 1062-1078.

Rahlao, Sebataolo, Brian Mantlana, Harald Winkler and Tony Knowles (2012). “South Africa’s national REDD+ initiative: assessing the potential of the forestry sector on climate change mitigation”, Environmental Science & Policy. 17, 24-32.

Zetterberg, Lars (2012). “Linking the Emission Trading Systems in EU and California”, FORES Study 2012:6, Stockholm: FORES.